Where are the next big waves?

The search for new technologies and the next drivers of innovation

Riding Waves

The most impactful and largest startup outcomes arise from betting on small waves on the horizon that become big waves. These waves are typically technological breakthroughs that act as force multipliers for founders.

There have been many examples of this. Microsoft partnered with IBM to be the first OS for the personal computer in 1980 and rode the personal computing wave, profitably scaling to $100mm in annual revenue by 1984 and capturing 90% market share of all PCs by the early 1990s.

Amazon was founded in 1994 within months of the launch of Netscape, the first internet browser, and benefited from the rise of the internet to reach $100 million in run-rate sales within 2 years.

Instagram and Uber both launched in 2010, less than 3 years after the creation of the App Store. Both companies rode the mobile wave and benefited from tremendous organic growth as new smartphone owners sought out applications. This allowed Instagram to reach 25 million registered users within 18 months of launch and allowed Uber to reach $1 billion in run-rate bookings within 3 years of going live.

Still Water

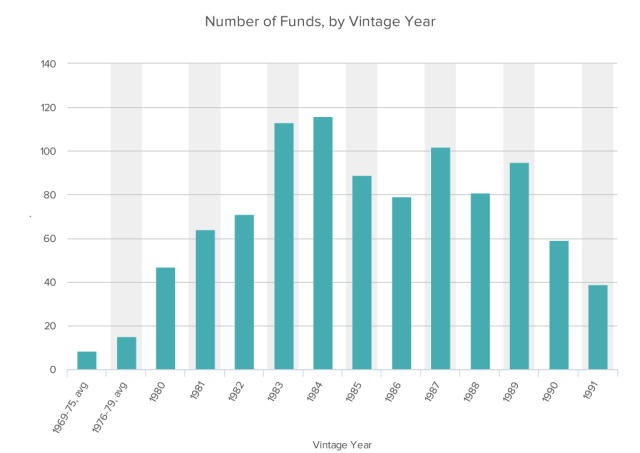

There have also been examples of lost periods of innovation. Looking at the US venture market, this was most pronounced in the early-to-mid 1980s. The boom times of the personal computing and software era were waning and the internet era had yet to arrive.

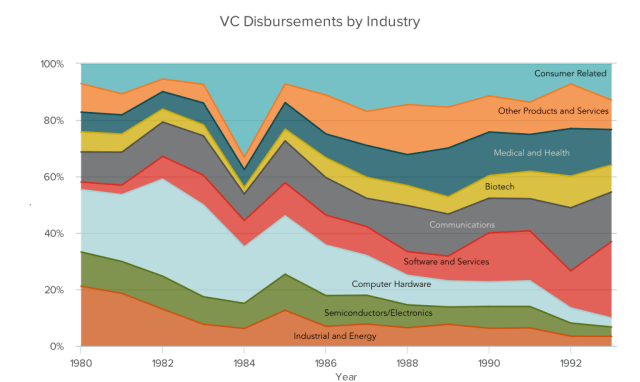

With record amounts of venture firms being started and an abundance of capital available (in part due to new regulations allowing endowments and pension funds to invest in the asset class), the venture industry sought to manufacture repeatable returns within new sectors and with new strategies. Capital shifted away from traditional technology to consumer goods, retail, healthcare, and biotech. Investors also began allocating more capital towards later-stage investments and buyouts.

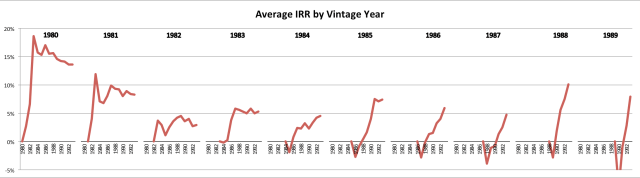

It didn’t end well. A more competitive investing environment, a saturation of companies in existing markets, the nascency of new markets, and the lack of a compelling exit environment all led to subpar returns for the venture asset class.

Receding Tide

2022 looks a lot like the beginning of the unproductive period in the early 1980s. The number of venture firms and AUM have exploded in recent years, both increasing by ~3x since 2014. Capital deployed has increased 7x in that time frame. Competition between investors has never been higher.

Similarly, investors have concentrated capital in the most productive sectors and into later stages. In place of computer hardware, the focus has been on software, with the sector accounting for ~40% of all investment in 2021. Late-stage investing has become a bigger focus and accounted for 70% of total capital deployed.

Lastly, the door has shut on the most compelling exit environment in history, one in which we saw more IPOs and SPACs in the past 2 years than the previous 10 years combined.

While history doesn’t repeat, it often rhymes. Without a new wave of innovation, investors flush with dry powder are likely to chase returns in less productive industries. Is software still the future? What comes next? Are we headed to a decade of subpar returns and outcomes for investors and founders alike?

The Search for the Next Wave

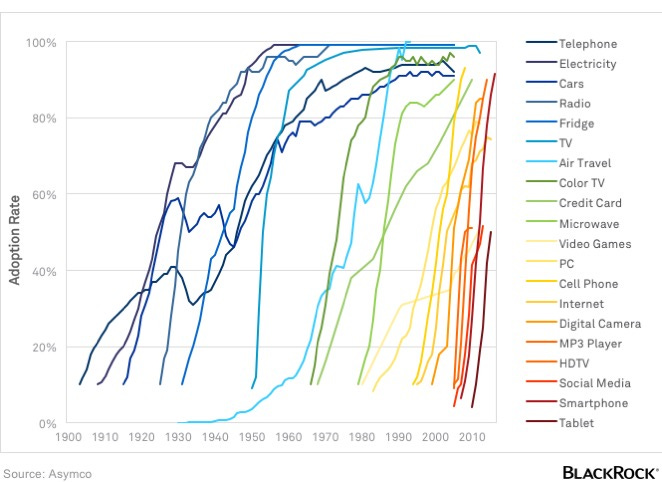

The arc of technological change is long. The combustion engine was invented in 1872 and went on to rearchitect the US economy over the next 100+ years to one led by cars as the primary form of transportation.

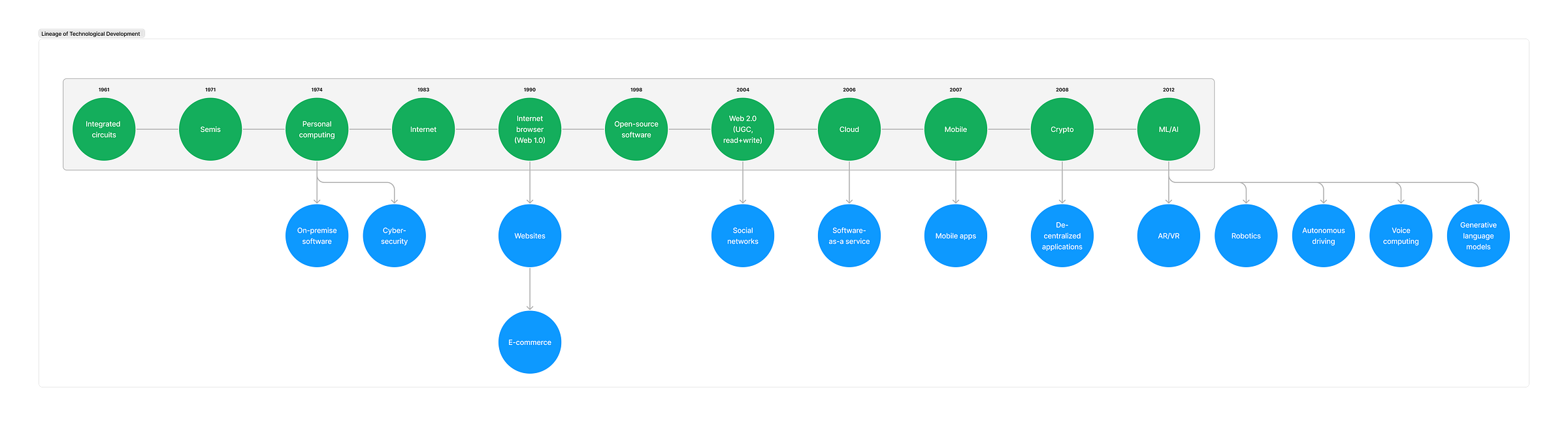

The equivalent moments for the contemporary technology industry were the invention of the integrated circuit in 1961 and the invention of the internet browser in 1995. These innovations led to a series of additional breakthroughs that transformed how we access computing resources, conduct work, communicate with each other, create software, and distribute products. Notably, each new technology was built on the prior: the rise of integrated circuits enabled the rise of personal computing, which supported the rise of the internet, which enabled the rise of cloud, which supported the rise of the smartphone.

Each of these innovations created derivative opportunities as well. The adoption of technology and software created new attack vectors for bad actors and led to the emergence of cybersecurity. The proliferation of mobile devices and the cloud led to an abundance of data and compute, giving rise to machine learning and AI. The trustless nature of the internet led to advancements in cryptography and new consensus mechanisms.

We are only 60 years into the tech revolution and history would point to more opportunity ahead. At the same time, technology has been adopted faster than previous innovations and with the record amounts of venture dollars being deployed, existing markets are quickly becoming crowded while new technologies have yet to break out.

Mobile is saturated. The cloud is still growing rapidly but is more of a red ocean at this point, where new software companies offer marginal improvements to existing solutions and focus more on distribution than innovation. Sure there is room to improve these technologies — making them better, faster, cheaper, safer, and more reliable — but these are incremental problems that require incremental solutions.

New markets fare no better. Virtual/augmented reality is in its infancy and has not broken through to the masses yet (and may never do so). Crypto has some potential energy for disruption, particularly within financial services, but is stuck in a speculative mania with minimal utility on offer today. AI and robotics have the potential to increase automation and economic productivity but will take a long time to overcome issues with edge cases (humans are quite malleable after all), capital intensity, and long timelines for implementation.

In many ways, it feels like the abundance of capital has led to investors trying to catalyze nascent markets and bring them to the masses, in essence serving as outsourced R&D. This is in sharp contrast to prior eras in technology, where emerging markets — ones with proven and sustainable business models — catalyzed venture returns. All of this has implications for founders and investors alike. If being an early participant in a breakout technological shift is a necessary condition for large outcomes and significant impact, we might be heading to another lost decade.

Looking Out at the Horizon

The advancements of the past two centuries created tremendous efficiency and abundance, from transporting ourselves anywhere on a whim to being able to access information at our fingertips to instantaneously connecting with anyone across the globe.

If anything, I believe the waves of the next century will revolve around fostering sustainability. New technologies will be required to address acute societal problems. We will need innovation to address our looming climate crisis and help society transition to a greener grid. We will need to find ways to increase longevity and prevent disease. We will need to find new ways to increase productivity as we face future demographic declines.

Unlike the past decade, many of these problems will require innovation with atoms in addition to bits, akin to the birth of the microchip industry. In this regard, the future might look a lot like the past. The government — specifically NASA and the Air Force — was the first buyer of resort for integrated circuits in the 1960s, allowing the industry to justify significant capital investment. Similar things are happening today with the passing of the Inflation Reduction Act, with the government providing subsidies, grants, and tax incentives for clean technologies (EVs, heat pumps, solar panels, etc.). Perhaps this will prove to be the inflection point for climate-focused startups.

The search for the next wave continues.

Thank you to Damir Becirovic and Vinay Hiremath for providing feedback.

Sources:

http://reactionwheel.net/2015/01/80s-vc.html

NVCA Yearbook 2015-2016, 2019-2022

Great read! One thought:

The multi-decade transitionary solution to the ‘climate crisis’ is natural gas and nuclear energy. It always has been, yet this pathway has been neglected in favor of political jousting and fear-mongering. There is no silver bullet here.